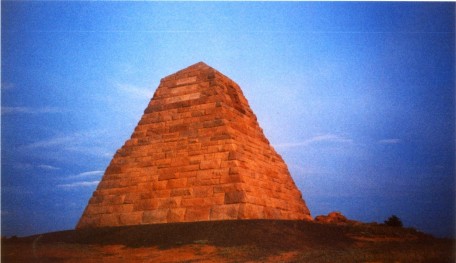

The Ames Monument, built to mark the highest elevation of the original transcontinental railroad, 8,247 feet.

A STRETCH of concrete, running roughly perpendicular to the embankment of US-30, would have passed by the car window unnoticed if Matt West hadn’t pointed it out. We were driving across Wyoming and Matt West, a teacher of ceramics and art at Laramie County Community College in Cheyenne, was our unofficial tour guide.

He pulled onto the shoulder. Walking down the embankment and climbing a small fence, we stood on a strip of concrete about 15 feet wide. It didn’t look like much—perhaps a narrow parking lot, or a concrete apron around some lost factory or school. Weeds grew up between cracks in the pavement.

It was a sample mile of the Lincoln Highway. Begun in 1913 (a coast-to-coast drive is set to mark its centennial in June), it was the first transcontinental highway in the United States. The Lincoln Highway was the idea of Indianapolis Motor Speedway founder and automotive entrepreneur Carl G. Fisher, with help from Frank Seiberling, president of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., and Henry B. Joy, president of Packard Motor Co. The Lincoln Highway Association would work with municipalities to erect a sample mile of road outside of a town, in an effort to entice the state to build the rest. The promotion worked, and the road was built across the entire length of the country, but some of the sample miles, like this one, were never incorporated into the final road.

The Lincoln Highway followed the route of the transcontinental railroad, which is largely responsible for the existence of Cheyenne, and many other cities. During construction, the Union Pacific Railroad established camps for its workers every 50 miles or so along the right of way. Some of these camps faded away, but many turned into the present-day cities of Wyoming. Just look at the mileage chart in your road atlas. The distance from Sidney, Nebraska, to Cheyenne—100 miles. Cheyenne to Laramie—49.4 miles. Laramie to Rawlins—99.9 miles. Rawlins to Rock Springs—107 miles. Rock Springs to Evanston—104 miles.

Getting back in the car, we merged onto Interstate 80, the first coast-to-coast interstate highway, completed in 1986. It absorbed some of the Lincoln Highway and follows the transcontinental railroad closely. Like the two earlier transcontinental routes, I-80 runs contiguously from New York City to San Francisco.

Between Cheyenne and Laramie the landscape seems to flow, the land undulating with rock formations and scrubby plains. From beneath a rise in the plain a distinctly unnatural shape pokes above the surface of the earth. It looks like the stuff of conspiracy theories—something from another world or a lost civilization, captivatingly inexplicable. Exiting the interstate, West directs the car onto a paved one-lane road, then a dirt road. The country around us is barren—no trees, no buildings, a few houses in the middle distance, and the rolling brown mountains beyond. A stone pyramid heaves into view.

Built in 1882 by the Union Pacific Railroad, the pyramid marks the highest elevation of the original transcontinental railroad, 8,247 feet. It stands 60 feet tall and 60 feet wide, and is made of granite blocks quarried nearby. The pyramid also serves as a monument to the Ames brothers of Massachusetts—Oakes (1804-1873) and Oliver (1807-1877), owners and backers of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Bas-reliefs of the two brothers, by the prominent 19th-century American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, adorn the top of the Ames Monument, as it is officially called. Saint-Gaudens sculpted memorials for Abraham Lincoln, Peter Cooper, and William Tecumseh Sherman in cities like New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C. But his reliefs of the Ames brothers are seemingly without an audience, gazing not at an opulent metropolis, but at the badlands of Wyoming.

The sample mile and the Ames Monument both leave visitors with a sense of something more than their specific historical significance. In the narratives of the transcontinental railroad, Lincoln Highway, and I-80, Wyoming figures not as a destination, but as a place on the way to somewhere else. The sample mile and the Ames Monument are somehow lost, without context. And today these monuments seem to stand not for a logistical achievement, but for the feeling of being passed by.

Another view of the Ames Monument, located off US-30 and I-80, between Cheyenne and Laramie, Wyoming.